From Idea to Product Launch: How to Build an MVP Experiment

Context

How did Amazon, Airbnb and Dropbox successfully grow into billion dollar companies? Spoiler alert: they started with minimum viable products (MVP).

The 3 companies mentioned above are startup success stories, which account for less than 10% of cases nowadays. According to CBInsights, the main reason why startups fail is due to misreading market demand (42%). You might have the best new product idea in town, but if you don’t find the right customers and markets for it, it will result in a failed product and perhaps even a failed business. This is where an MVP comes in to save the day.

Eric Ries, who introduced the concept of MVP in his Lean Startup methodology, explains that “the minimum viable product is that version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least amount of effort”.

In other words, an MVP is a product with just enough essential features to attract early adopters to use it in order to validate your product idea early in the product development cycle. It’s not a finished product, it’s only the first version. You launch it, you collect feedback, you learn what works and what doesn’t, you iterate on what works and discontinue what doesn’t work.

MVP Experiment Steps

Conducting an MVP Experiment is a process which results in validating or invalidating your product idea.

Identify the need

First you need to identify market gaps or the problem your product solves, either for your company or for customers.

Determine the long-term goal

Why are you building this product? What are you trying to accomplish? Note down your long-term goal and let it guide you throughout the entire process.

Identify the minimum criteria for success

List the criteria that will determine whether or not your product will be successful. The criteria you list here links to the long-term goal you are trying to achieve.

Example:

Positive gross profit margin by the end of first year

Having 100,000 active monthly users after 6 months since launch

Having a 1.5% conversion rate by the end of first year

Reaching $1M in monthly transactions by the end of first year

Identify the target market

These are the end-users who will be using (and preferably) pay for your product.

A good way to find potential users is to follow the template below:

My solution does:

Function #1

Function #2

Solves:

Problem #1

Problem #2

For:

User group #1

User group #2

You want to address your MVP to that group of users who are most likely to adopt it.

In each user group, it’s possible that you will have more than one user persona who will benefit from your product. When crafting a persona, you are interested in any traits of the end user that might impact their product usage: geographics, demographics and psychographics (behaviors).

Research your competition

Now that you have a clear perspective over what you’re trying to build, it’s time to check what the neighbours are doing. For each competitor, you want to find out:

Market size: how big is the market

Growth: whether the competitors are growing or declining

Funding: whether they are raising money from venture capitalists

Features: how they are solving the problem that you’re addressing

Marketing strategy: who they are targeting, on what channels

Customer sentiment: how much customers like their products

Professionalism: overall how trustworthy their website and product feels like

Your end goal at this stage is to identify if there is room for your product into the existing market and what are your differentiators.

Craft your hypothesis

If you’ve discovered that there’s an opportunity for your product at the previous step, the next thing to do is to note down your product idea and reduce it to a hypothesis that encapsulates what you’re trying to achieve with your product. The entire MVP experiment will be built around testing this hypothesis.

Format: I believe that user_persona will do_action because reason

Example: I believe that dog owners will pay and use a service to get their dogs walked because they’re busy.

Conduct customer research

Now that you’ve identified what problem your solution is solving and for whom, talk to your prospective customers by conducting interviews. Your goal is to find out if this is a real problem for them and if yes, how big of a problem it is and how they are currently solving it right now: what other solutions or workarounds they are using, how often and in what circumstances.

If after this stage, you realize that your assumptions and hypothesis are invalidated, you can pivot:

either by solving a different problem and you’re back at step 1

or by conducting customer research interviews for the second most likely target users you have identified at step 4

Identify the user journey

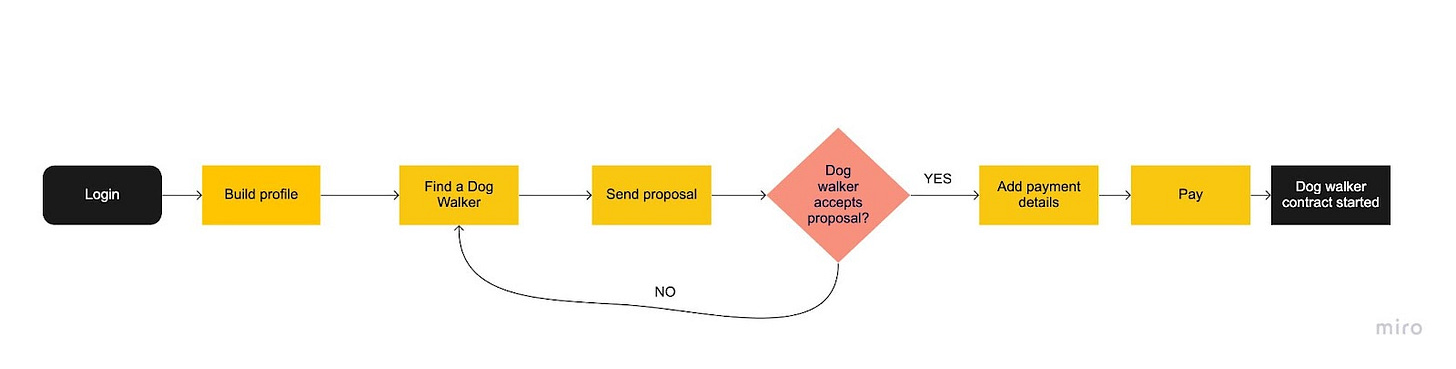

Assuming you passed the previous step, then you should map the user journey for each user persona. The user journey should list all the actions/ steps the end user is required to take in order to achieve their goal.

Basic user journey for finding a dog-walker through the dog-walking app:

In order to make sure you are building only the essential features, you can list all the actions from your user journey and map each action based on a pay and gain map: how big is the pain versus how much value the user is receiving when that pain is addressed.

Example:

Action: Find a Dog Walker

Pain: Trouble finding the availability of dog walkers

Gain: View available dog walkers and book immediately

For each user persona, count the number of pains and gains for each action. Ideally, when it makes sense, you should assign a value using a point system to help quantify the importance/ impact of each gain.

Decide what features to build

Transform the pains into opportunities

You can do this by using the “How might we” format: How might we make it easier to book dog walkers? At this stage, you want to transform the pains and gains into features.

Prioritize your features

Use a prioritization matrix (effort vs impact) or something similar to prioritize the most impactful features. Remember that you’re interested in the minimum amount of features to validate your idea. When prioritizing, always keep in mind the long-term goal of your product.

Develop the actual MVP

This is the step where your actual minimum viable product is being built.

Market your MVP to the target users

After your MVP is released, you should start targeting your early adopters: the user personas you have identified at step 4. This is the real experiment and you want to get as much feedback as possible: both quantitative and qualitative.

From this point on, you want to start measuring how your product is behaving against your success metrics.

Analyze experiment results

At this stage you need to do some checks:

Are your assumptions and hypothesis validated?

Did you target the right users at step 11?

Are your users using the product the way you imagined it would be?

Did all your success metrics pass?

This is the step where you analyze if your experiment worked or not and compare your results against the success metrics you listed at step 3.

Iterate or drop it

Based on the results of your analysis, you should decide at this stage whether you iterate the MVP to a new version or drop it altogether.

Summary

MVP does not mean a bad version of your first product, nor the least amount of effort to launch your product. It means investing the minimum required resources to get you to the point where the customer says YES or NO: I’m interested or not in your product.

MVP experiments can be applied to business initiatives, new product/ service launches as well as new features for existing products.

Besides allowing you to validate an idea/ assumption for a product without building the entire thing, an MVP experiment also helps in minimizing the resources involved (time, budget) that you might otherwise have to commit to for developing a product that won’t succeed.

Resources & Further Reading

Eric Ries, The Lean Startup (2011)